I think it is truly wonderful that three pensioners from the Royal Hospital Chelsea in London, should travel a little over three thousand miles to attend an act of remembrance with us here in Bahrain. As someone who has served, remembrance parades and services gives many of us the opportunity to remember those old comrades and those unknown soldiers who gave their lives and to reflect on those who are still giving their lives, so that we might live in a better place today.

I think it is truly wonderful that three pensioners from the Royal Hospital Chelsea in London, should travel a little over three thousand miles to attend an act of remembrance with us here in Bahrain. As someone who has served, remembrance parades and services gives many of us the opportunity to remember those old comrades and those unknown soldiers who gave their lives and to reflect on those who are still giving their lives, so that we might live in a better place today.

Remembrance Day is widely observed on 11 November to recall the end of the hostilities of World War I on that date in 1918, when the fighting formally ended “at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month”, with the signing of the Armistice. I remember my grandfather telling me how strange it was when the guns fell silent to be followed by the men cheering in their trenches. The Red poppy has become the symbol of remembrance since these poppies bloomed across the battlefields of Flanders and their bright red colour has become symbolic of the blood shed during wars.

Whenever I hear of Flanders, my mind is taken back to my days at Sandhurst, where my training Company was Ypres, which is a town located in the west of Belgium that has a poignant significance in the First World War. There were five battles for Ypres, the first (1914) halted the German drive to the channel ports, the famous 2nd battle which saw the first effective use of poison gas against enemy troops. For the record, the French were the first to deploy gas against the enemy (1), but this was in the form of tear gas grenades and was designed as an irritant to disorient the enemy, not to kill them. In reality, the use of poison gas did not result in a significant loss of life compared to other casualty statistics, but the psychological effect was significant. The third battle of Ypres was the famous Battle of Passchendaele (1917) where nearly half a million soldiers lost their lives over the course of three months and six days. The fourth battle was the battle of Lys (1918) and the fifth battle of Ypres was the advance of Flanders (1918) that eventually secured Ypres with the armistice being signed a little over a month later.

I sometimes wonder how difficult it must have been!

I spent several years commanding troops and I know from experience how difficult it is to operate in the rain soaked terrain of Western Europe. But compared with today, these guys didn’t have many vehicles and they didn’t have the technology that we take for granted today. Air support didn’t exist until later in the war, neither did tank support – so soldiers marched as units along with all their kit. Soldiers cannot fight without rations, equipment and munitions and the Army Service Corps was one of the great military achievements of the First World War – Supply Chain Logistics was invented here.

Today, we live in a society where we expect food and drinks to be fresh and to have been kept refrigerated with sell by dates and tracking to ensure the foods suitability for consumption. A hundred years ago, the troops in the trenches were lucky to get bully beef and vegetable stew from the cooking shelter and they also had to contend with rats, flies, flooding, smelly latrines, cold during the winter and of course the enemy shooting at them. It has been estimated that bread could take up to eight days to reach the front-line and if the enemy shelled the supply lines, they didn’t get any rations for days on end.

Communication was another significant problem. You can only shout so far and the other noises on a battle field can render this method of communications ineffective. Signs need to be seen and understood, whistle blasts and sirens have to have a meaning, usually attack, retreat and gas attack or all clear. How did they communicate their ration, equipment and Ammunition requirements? They used the Company Runner, who would brave bullets, shells, mayhem and muck to move messages both forwards and backwards to forward and rear operations positions. They also used telephones, but invariably this form of communications suffered from the lines being disrupted by shellfire and the signals lineman had to brave a storm of bullets and shrapnel in order to restore the broken lines. Both sides also used pigeons and dogs to carry messages, most usually in dire circumstances and not always successfully although some statistics suggest an above 90% success rate.

Communication was another significant problem. You can only shout so far and the other noises on a battle field can render this method of communications ineffective. Signs need to be seen and understood, whistle blasts and sirens have to have a meaning, usually attack, retreat and gas attack or all clear. How did they communicate their ration, equipment and Ammunition requirements? They used the Company Runner, who would brave bullets, shells, mayhem and muck to move messages both forwards and backwards to forward and rear operations positions. They also used telephones, but invariably this form of communications suffered from the lines being disrupted by shellfire and the signals lineman had to brave a storm of bullets and shrapnel in order to restore the broken lines. Both sides also used pigeons and dogs to carry messages, most usually in dire circumstances and not always successfully although some statistics suggest an above 90% success rate.

At the beginning of the war, wireless transmitters were mainly cumbersome unreliable spark transmitters, but towards the end of the war, radio was developed to a point where its use was more commonplace on the battlefields, although still heavy, prone to failure and reliant upon a good operator. That being said, many of my fellow Signals Officers firmly believe that the advent of wireless communications on the battlefield significantly enabled resource management principles and therefore inadvertently contributed to the demise of trench warfare.

Today, One hundred years later, you can pick up a mobile phone that is about the size of a packet of playing cards, but thinner and weighing on average between 100 and 150 grams with which you can talk to your family and friends in a far distant land you call home and not even wonder at how ubiquitous this technology has become.

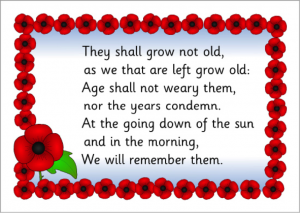

Please take a moment to reflect the immortal words of Binyon’s classic poem, “For the Fallen”,

Image – http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/4541-4550/sb4548.html#.VHr7MskXKO8

For all those serving…. I salute you!

[su_divider top=”no”]

- “Poison Gas and World War One”. HistoryLearningSite.co.uk. 2014. Web.